William Wright Company Commissions

For many decades the William Wright Company’s name was synonymous with Detroit luxury. Founded in the 1857 by English immigrant decorative painter William Wright, the firm endured until almost the end of the Great Depression in 1939.

Sadly, Wright company records are not known to have survived. In order to understand the breadth and scope of the firm’s work, historians spent months combing through American and Canadian publications in hopes of identifying “new” Wright commissions. This portion of the Art Adorns the Paths of Life project features their discoveries, which together comprise the first modern Wright Company catalogue raisonné.

Scroll the list of known commissions below and click on each list to learn more!

Boats

Lovely Escapes on the Water

William Wright spent more time near water than the average 19th century businessowner. Born on an island, Wright chose to establish his business in riverside Detroit and live on a waterfront farm in Canada. As someone who commuted between work and home every day via ferry, his life was interwoven with watercraft.

Fittingly, the Wright Company decorated a number of boat interiors. They ranged from private luxury yachts to passenger steamers that also hauled freight. Some carried travelers on multi-week excursions, while others made short, repetitive runs to nearby islands. For many Michiganders, their most well-known nautical commission was for the Columbia – a Boblo boat.

Cibola (1887)

City of Alpena II (1893)

City of Erie (1898)

Galatea (1914)

Helene (c. 1931)

SS Columbia, Bob-lo (1902)

Steamer Dove (1868)

Steamer Pennsylvania (1899)

Commerce

“Handsome, Convenient, and Up-to-Date”

What is the purpose of a beautiful business or commercial center? Is it to trumpet success and herald the wealth of its owner? To make customers feel that they are part of a select, exclusive clientele? To create an otherworldly atmosphere? To convey the sense that this business understands the value of aesthetics and investment?

Whatever their motivations, many businesspeople hired the Wright Company to decorate their interiors. Using paint, marble, mirrors, wood, and imported European antiques, Wright artisans transformed staid storefronts and meeting rooms into something special. Simply put, buying and selling was different when done in a Wright commission.

John Breitmeyer’s Sons’ Flower Store (Detroit - 1905)

Detroit Board of Trade (1879)

Pingree & Smith Shoe Company (Detroit - 1892)

Detroit National Bank, Buhl Block (Detroit - 1894)

Savings Bank of East Saginaw (Saginaw - 1903)

E.B. Smith & Company (Detroit - 1868)

Grellings Photo Gallery (Detroit - 1870)

August Frank Lunch Stand (Detroit - 1879)

Fisher Building Offices (Detroit - 1920)

Wayne County & Homes Savings Bank (Detroit - 1905)

Kuhn Confectionary (Detroit - 1909)

Basement Cafe in Hammond Building (Detroit - 1912)

The Commercial Bank (Port Huron - 1905)

People’s Building & Loan Association (Saginaw - 1931)

Churches

Heavenly Beauty

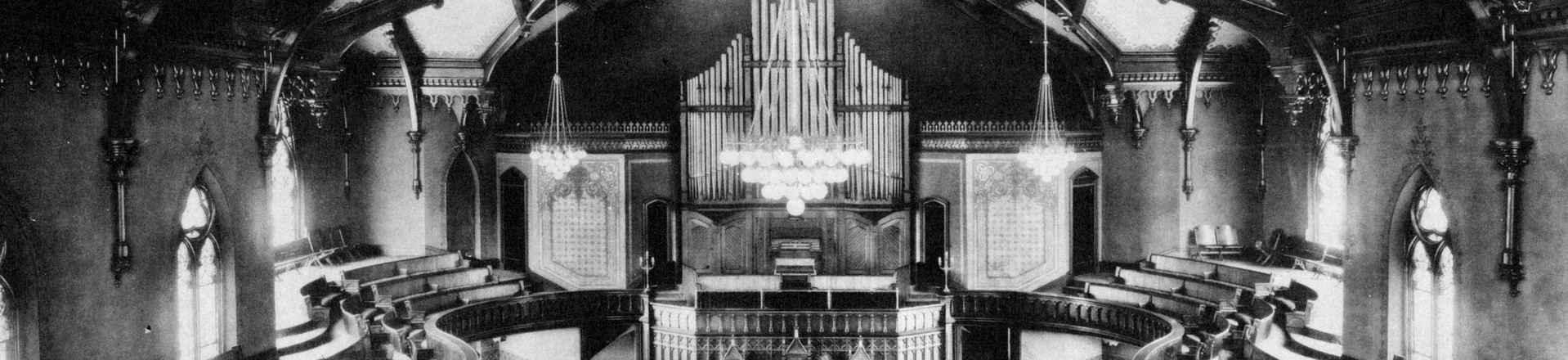

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, churches ranked among the most highly decorated buildings in America. Growing congregations built elaborate brick and stone structures that evoked permanency and strength. Many incorporated elements of much older European styles associated with religious architecture, including Gothic and Romanesque Styles. Reinterpreted by American architects, these buildings are today classed as Victorian Gothic, Gothic Revival, or Richardsonian Romanesque Revival. Often they sit on traditional main streets, in easy to find locations.

Many of these now-historic churches contained large, elaborately decorated sanctuaries where parishioners met for weekly worship. Everything within, from their marble alters to the wooden pews, stained glass, and brass chandeliers, was designed to reflect the majesty of the Divine. While different denominations might have specific traditions or rules regarding art forms, all wanted something special. The best sanctuaries made worshippers feel they’d been transported to a veritable heaven on earth.

First Presbyterian Church (Detroit - 1860 & 1879)

First Presbyterian Church (Detroit - 1889)

St. Mark’s English Lutheran Church (Detroit - 1896)

St. Mark’s Episcopal Church (Grand Rapids -1902)

Fort St. Presbyterian Church Parish House (Detroit - 1908)

Fountain Street Church (Grand Rapids - 1904)

Howell Baptist Church (Howell - 1887)

Milford Presbyterian Church (Milford - 1905)

Port Huron Congregational Church (Port Huron - c. 1885)

St. John’s Episcopal Church (Detroit - 1873)

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (Flint - 1873)

Wyandotte Congregational Church (Wyandotte - 1903)

Clubs

Luxurious Retreats

Private clubs have long been places of upper-class sociability and networking. Formed by society leaders, for society leaders, these clubs were built on notions of exclusivity, power, and wealth. They were where men – and occasionally women – went to relax, dine, converse, and be entertained within the comfort of their own circles, away from the glare of public view.

The same money that fueled successful businesses and built mansions also filled club coffers. Thus, the same people who hired the Wright Co. to decorate and furnish their homes, churches, businesses, and yachts naturally entrusted them with their club interiors. Who could possibly want anything less?

Detroit Young Men’s Society Library (Detroit - 1868)

Detroit Club (Detroit - 1892, 1910)

Grand Rapids Masonic Temple (Grand Rapids -1895)

Detroit Socialer Turnverein Hall or Turner Hall (1897)

Knights Templar Commandery Asylum (Detroit - 1877)

Peninsular Club (Grand Rapids - 1883)

Toledo Club (Toledo, OH - 1891)

Government

Pride in Progress

Nineteenth century Americas took great pride in the world they created. Many believed it their duty to constantly improve both the natural and the built environments. Not surprisingly, this enthusiasm often manifested itself in the construction and elaborate decoration of major government buildings.

The architects and contractors who erected these government structures believed they were creating buildings that would stand the test of time. This was particularly important in post Civil War America, when Unionists wanted their government to project authority, stability, and continuity. Sadly, despite their intentions, many of the structures they built stood for only a few decades.

U.S. Customs House & Post Office Building (Detroit - 1898)

Michigan State Capitol Building (Lansing - 1885-1891)

Helping & Healing

Helping and Healing

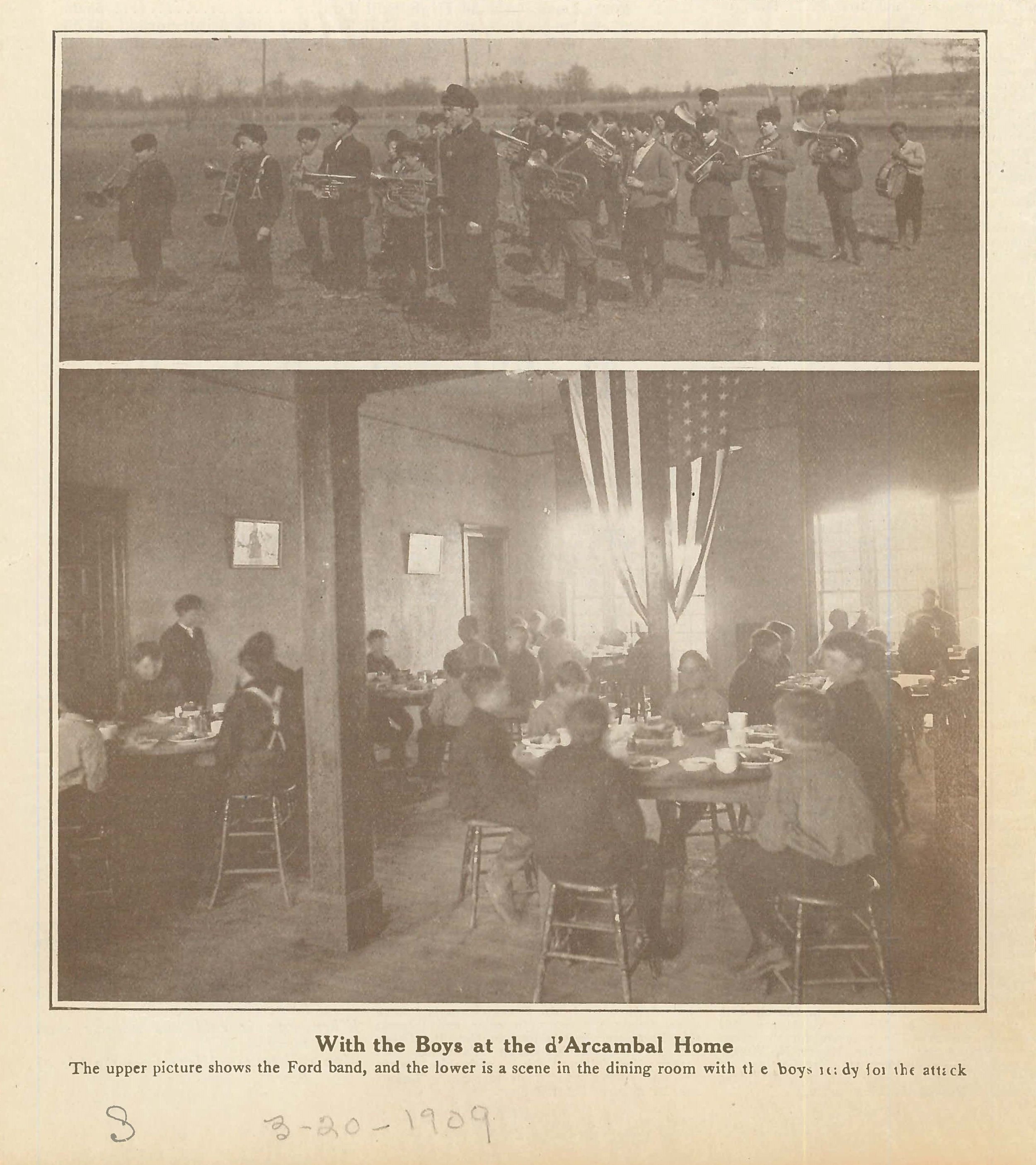

Before the creation of widespread, government-backed social services, sick and struggling Americans were reliant on the generosity of their neighbors for basic care. In many communities, upper-class women banded together to found small, private hospitals, halfway houses, and city missions focused on providing basic services and support to people in need.

Funding for these institutions, which often provided free or dramatically reduced-rate services, depended on the generosity of their board members, religious congregations, and other charitably inclined community members. It naturally behooved successful firms, like the William Wright Company, to demonstrate their support for such ventures (which were often backed by their wealthy clientele).

Home of Industry (Detroit - 1891)

Women’s Hospital and Foundlings Home (Detroit - 1892)

Methodist Deaconess Home (Detroit – 1905)

Homes

A Man’s Home is His Castle

The idea that a man’s home is his castle is said to date from ancient Rome. The ability to own property and live in one’s own home are also central to American identity. From colonial times onward, wealthy Americans celebrated their success by commissioning impressive homes that combined large areas for entertaining with private family and staff living quarters.

The nouveau riche of the Gilded Age kept up this tradition. Mining and lumber barons, manufacturing giants, and even successful entertainers spent lavishly on stately homes. Some might own three or four, scattered across different communities and states. Beautiful inside and out, the construction and decoration of these modern “castles” kept many architects, builders, artisans, and craftspeople busy for years.

John G. O’Neil Home (Port Huron - c. 1890s)

George & Katherine Barbour Home Addition (Detroit – 1900)

Theodore & Julia Buhl Summer Home (Peche Island – 1903)

Solomon & Caroline Dresser Home (Bradford, PA – 1903)

Christian & Maria Weidemann Home (Detroit – 1905)

Orlando Mack & Amanda Barnes Home (Lansing - 1876)

Judge H.B. Brown Home (Detroit - 1885)

Theodore & Julia Buhl Home (Detroit – 1899)

George A. Beaton Home (Detroit – 1900)

Hamilton & Annette Carhartt Home (Metro Detroit – n.d.)

E.P. & Mary Hanchett Stone Home (Saginaw – n.d.)

Virginia Park Home (Detroit – n.d.)

Henry Cheever Home (Detroit - 1868)

Burnham & Elizabeth Colburn Home (Detroit - 1905)

Edward & Adelaide Fisher Home (Detroit – 1923)

Lawrence & Margaret Fisher Home (Detroit – 1928)

Five Cleveland Homes (Cleveland, OH - 1886)

Charles Lang Freer Home (Detroit - 1890)

Col. Frank J. Hecker Home (Detroit - 1891)

“Senator Somebody’s” Home (Toronto, ON, CA - 1891)

A Capitalist’s Home (Chicago, IL - 1891)

May Irwin Summer Home (Irwin Island, ON, CA - 1907)

Sara and David C. Whitney Jr. Home (Detroit - 1894)

C.H. Davis Home (Saginaw - 1899)

Hotels

Fashionable Hospitality

One mark of America’s growing middle class was the ability to travel for pleasure. Travel required leisure time, money, and access to good transportation via railroads, steamboats, and improved roads. Whereas travel was once simply a task or a means to an end, now it could and was increasingly undertaken for the joy of the experience.

The rise of travel brought a growing demand for fashionable, up-to-date hotels where vacationers and businesspeople could relax and enjoy a change of scenery. It also heralded the growth of conferences and conventions, which brought the promise of hundreds of rooms booked at one time. Additionally, some hotels offered apartment suites where some people chose to make their homes. Naturally, prominent hotels worked to maintain reputations as up-to-date, fashionable, and hospitable destinations in hopes of attracting a steady clientele.

The Book Cadillac (Detroit - 1924)

The Cadillac Hotel Cafes (Detroit - 1902)

The Morton House (Grand Rapids - 1908)

The Russell House (Detroit - 1871, 1874, 1883)

VanDyne House (Lansing - 1886)

The Wayne Hotel Dining Room (Detroit - 1905)

The Wenonah Hotel (Bay City - 1908)

Special Events

Ephemeral Elegance

(Events, Exhibitions, and Temporary Decorations)

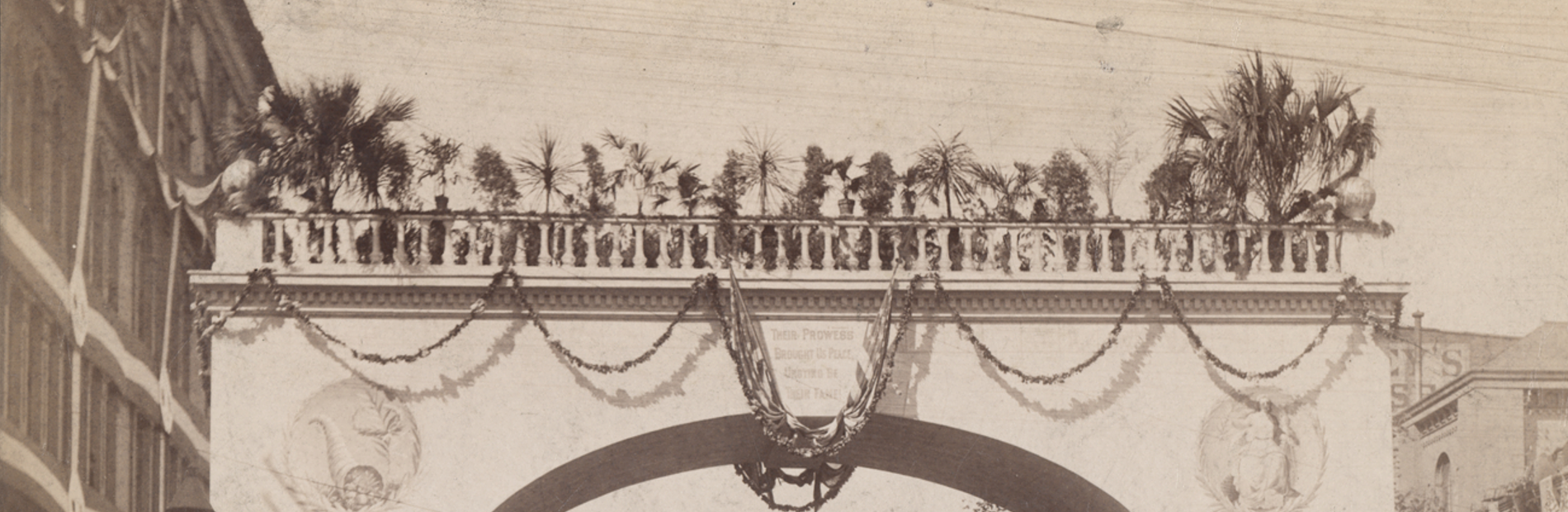

The William Wright Company was in the business of making things more beautiful and elegant. However, not everything they created was meant to last. Some commissions were ephemeral, created for a single evening, or a short, multi-week installation.

Doubtlessly, many of these commissions were related to other larger and more permanent jobs. Like any contractor, Wright never knew when a small example of well-done work could lead to other, much bigger, and more lucrative, jobs. Once a client was pleased, he or she naturally had the potential to commission more work in the future.

Detroit Boat Club (1868)

Detroit Art Loan Exhibition (1883)

Detroit Museum of Art (1885)

Chrysanthemum Flower Show (Detroit - 1889)

G.A.R. Arch of Peace (Detroit - 1891)

Detroit Chamber of Commerce (1892)

Detroit Children’s Free Hospital (1892)

Columbian Exposition (Chicago, IL - 1893)

Michigan Business Men’s Association (Detroit - 1898)

Michigan Women’s Press Club (Detroit - 1899)

Saginaw Art Club (Saginaw - 1904)

Theodore Buhl Housewarming Party (Detroit - c. 1907)

Theatres

Spectacular Showplaces

As more and more Americans moved into cities, the growing middle and upper classes looked for entertaining ways to spend their evenings and weekends. Many bought tickets and subscriptions to plays, operas, vaudeville shows, and lecturers. By attending these events, which often combined entertainment with a thin veneer of education or self-improvement, aspiring men and women gained a sense of cultural polish.

Naturally, these big events necessitated big venues. Aspiring businessmen responded by investing in the construction and management of large, often glamorous, buildings capable of seating hundreds. Alternatively known as opera houses or theatres, they were designed to impress inside and out, providing a show long before the curtain rose.

The Grand Opera House (Detroit - 1886)

The Temple Theatre (Detroit - 1908)

Majestic Theatre (Detroit - n.d.)

Whitney’s Opera House (Detroit - 1875)

Edison Institute Museum Auditorium (Dearborn - 1931)